3.30.2004

Imagine

The following was written by Jamaica Kincaid. It was published in the "Notes and Comment" section of the November 19, 1979, issue of The New Yorker.

This morning, I was listening to the radio -- I mean, I was ironing my shirt and the radio was on -- and the disc jockey said that the Beatles were getting back together, that they were going to give a benefit concert for some important cause or other, and how great that would be. He said, "Can you imagine the Beatles back and playing together?" I imagined that, and while I was at it I imagined a number of other things. I imagined that I was in love with the man who discovered the principle of hydrogen bonding and that he was in love with me, too, and that it was all almost wonderful; I imagined that my favorite color was red and that my favorite words were "vivid," "astonishing," "enigmatic," "ennui," and "ululating"; I imagined that even though I hadn't died I was in Heaven; I imagined that all the people I didn't like were gathered up in one big barrel and rolled down from a high mountain into a deep, deep part of the sea; I imagined that all the books on my shelf had long legs and wore flesh-colored panty hose and that their long legs in the flesh-colored panty hose dangled from the bookshelf; I imagined that the trains in the subway had all the comforts of a private DC-9; I imagined that I had the most beautiful face in the whole world and that some men would faint after they got a good, close look at it; I imagined that I had different-colored underwear for every day of the year; I imagined that it was a real pleasure to be with me, because I was so much fun and always knew the right thing to say when the right thing needed to be said; I imagined that I knew by heart all the poems of William Wordsworth; I imagined that it rained only at night, starting just before I fell asleep, so that the sound of the rain would lull me to sleep, and that it stopped raining just before I woke up every morning; I imagined that I could run my tongue across the windowpane and not pick up, perhaps, some deadly germ; I imagined that all the people in the world were colored and that they all liked it a whole lot, because they could wear outlandishly styled clothes in outlandish colors and not feel ridiculous; and then I again imagined the Beatles back and playing together. None of it did a thing for me.

Peter Out

Peter Ustinov has died. The following is from the Age.

Already a celebrity before he turned 20, he was an actor, playwright, author, mimic, opera director, satirist, UNICEF ambassador, newspaper columnist and, above all, raconteur. Ustinov was to many the quintessential renaissance man.

He affected to being indolent, yet wrote 23 plays, 13 books and nine films, acted in 40 films and 20 plays, directed eight films, eight plays and 14 operas. He won two Oscars, three Emmy Awards and, despite his deep ambivalence towards Britain, accepted a knighthood in 1990. He spoke five languages fluently and a smattering of others.

Ustinov hankered to be taken seriously as a writer and commentator in Britain, as he was in Europe. But he seemed fated and eventually even resigned to playing the role of the fat, funny foreigner in his own country. To that end he was perhaps his own worst enemy - for as a storyteller, Ustinov was a very funny man indeed.

3.29.2004

Lip Service

Here you can listen to an interview with Yeardley Smith, the woman who gives tongue to Lisa Simpson. (There's also an interview with Nicholson Baker, author of such books as The Fermata and The Size of Thoughts.)

3.21.2004

Chips Ahoy!

The following is the first paragraph of Stephen Fry's introduction to his essay collection Paperweight.

Welcome to Paperweight. My first act must be to warn that it would be a madness in you to read this book straight through at one sitting, as though it were some gripping novel or ennobling biography. In the banquet of literature Paperweight aspires to be thought of as no more than a kind of literary guacamole into which the tired and hungry reader may from time to time wish to dip the tortilla chip of his or her curiosity. I will not be held responsible for the mental indigestion that is sure to be provoked by any attempt to bolt the thing whole. Snack books may not be the last word in style, but for those sated and blown by the truffles and quenelles of the master chefs in one kitchen, or flatulent with Whoppers and Super Supremes from the short-order cooks in the other, it may just be that Paperweight will find a place.

3.18.2004

Greene Acres

In this Fresh Air interview, Brian Greene explains how to travel a million years into the future.

Here's Fresh Air's Greene bio:

With his book The Elegant Universe, physicist Brian Greene developed a reputation for explaining complex scientific theories with insight and clarity. The book was the basis for a PBS series. His new book is The Fabric of the Cosmos: Space, Time, and the Texture of Reality. Greene is a professor of physics and mathematics at Columbia University. He received his undergraduate degree from Harvard and his doctorate from Oxford, where he was a Rhodes scholar.

3.16.2004

Funhouse Mirror

The following is from the September 21, 1998, issue of New York magazine.

"Jerry Seinfeld said something that I thought was very true -- people that think they're good-looking aren't funny," he [Conan O'Brien] says. "The thing I liked about that quote was that now I'm six four and 190 pounds, and they put some makeup on me for TV, and they put me in these nice suits, and occasionally women will write in and say, 'You're really good-looking.' That's not my self-image. Because in adolescence I was six four, 155 pounds, and had bad skin."

Phonin' Conan

The following is from the September 21, 1998, issue of New York magazine.

When I -- somewhat naïvely -- ask him whether he's friendly with the man he succeeded as host of NBC's Late Night, O'Brien shakes his head. "I really don't know Dave very well," he says. "When I first got the show, he called me up. There's a formality about him. Sort of an old-world gentility. He said, 'I'm not sure we've met. Have we met?' And I said, 'No, we haven't really met, Dave.' He was very nice. And at the end of the conversation -- I just couldn't help it, because he's such a big influence and everything -- I said the thing you're not supposed to. You know, 'It meant so much to me that you called; I'm a huge fan of your --' and I don't think I even got to finish the sentence. He said, 'Well, that's not why I called.'"

3.15.2004

Weide Load

In this informative Fresh Air interview, Curb Your Enthusiasm producer Robert Weide compares Larry David to Robert Benchley.

Faxing the Cracks

Here's a nifty little article -- from the November 1998 issue of Men's Fitness -- about writing jokes for late-night television. It was written by Lee Frank.

An excerpt:

Think writing jokes for a living is easy? Not on your life, Skippy.

Night after night, David Letterman does eight monologue jokes. No more, no less. And every night, I watch and wait for something familiar. One night, he surprises me by doing a ninth joke - and, yes, it's one I wrote. I say the lines right along with him:

"The Hong Kong flu, it's killing people, and as a result, the government has to slaughter over a million chickens. Ooh! What are you going to do with a million dead chickens? Did somebody say McDonald's?"

Some guys sell shirts, some guys sell backhoes. As it happens, I sell jokes. Each day, I craft witticisms concerning current events and peddle them to the TV-comedy crowd: David Letterman, Dennis Miller, Jay Leno, Bill Maher, Colin Quinn, Rosie O'Donnell.

These people are busy knocking out their TV shows. You think they have time to stay up reading newspapers till dawn? Think they have the drive to stare at a blank computer screen and try to be funny until blood dribbles from their ears? That's where gag writers like me fit in.

Maybe you thought TV stars came up with their own material. Well, forget about it; the sheer volume of jokes they demand requires teamwork. (Jay Leno, for instance, will look at 100 jokes before deciding on the 14 he uses in his monologue.) So when you hear your favorite late-night host say something hilarious, chances are it was scribbled by someone else.

How do I feel when my work is attributed to a star - when, for instance, jokes I wrote for Dennis Miller are quoted in Entertainment Weekly as examples of how brilliant he is? Hey, pal, this is show business. Wear a cup. Get up and walk it off! I don't care if I never become famous from my own jokes, as long as they supply me with little luxuries like food and rent.

So, you think it's funny being a professional joke writer? Let me tell you about it, sweetheart.

Late night ... with me

First, I have to thank the fax machine, without which none of this would be possible. There have always been writers for monologue jokes. But with the advent of technology, shows can now tap a larger pool of talent. Freelance writers like me can work at home and instantly send jokes to programs' head writers. These shows want the best material they can get their hands on, and each has a stable of freelancers who're made it onto their "approved" fax list. (It took me two years before the Letterman staff would look at my stuff.) The big difference is that while the staff writers make the big TV dough, fleelancers get paid between 75 and 100 bucks a pop, and then only if a joke is used.

No, it's not much money. So I'm ever vigilant in my search for comedic fodder. I pore through five newspapers each night. I stay up until 4 in the morning, browsing the Net for breaking events. A former news junkie, I can't read a newspaper now without looking for jokes. Famine in the Sudan? Nothing funny there. Cyclone in India? Keep going. Airline crash in China? I think not.

System Upgrade

The following was published today in the Guardian.

New 'planet' discovered beyond Pluto

Press Association

Monday March 15, 2004

Scientists in the United States were expected to announce today that they had found a new "planet" in our solar system, after spotting a 10th heavenly body orbiting the sun.

After sightings by the Hubble telescope and the Spitzer space telescope, Nasa has announced that it would present the "discovery of the most distant object ever detected orbiting the sun".

The find was made by Dr Michael Brown, associate professor of planetary astronomy at the California Institute of Technology, in Pasadena, who is working on a Nasa-funded project, the organisation said.

The object has been named Sedna, after the Inuit goddess of the ocean.

The body is believed to be about 1,250 miles across, but may even be larger than the furthest known planet, Pluto, which was discovered in 1930 and has a diameter of 1,406 miles.

Scientists believe Sedna is 6.2bn miles from Earth, in a region of space known as the Kuiper Belt, which contains hundreds of other known bodies.

Whether the new discovery can actually be called a planet is likely to be debated by astrophysicists for months or even years to come. Many bodies of rock and ice exist in the region and there is still some argument over whether Pluto is a real planet.

3.12.2004

Merry Barry

My pal Claire Zulkey recently interviewed Dave Barry.

An excerpt:

Who are some of your favorite humor writers?

Steve Martin, Carl Hiaasen, Roy Blount Jr., Gene Weingarten, the late great Robert Benchley, the Onion people, and a bunch more whose names escape me now because EVERYTHING escapes me now except body fat.

When and why did you begin your blog? Is it a burden to keep up in addition to the columns and the books and the other projects?

I started it in early 2003 or thereabouts because Ken Layne ordered me to. Yeah, sometimes it's a hassle, but I'm learning not to fret about it when I have actual paying work to do.

With comedians, it seems like the funnier, the more morose in real life. Does that work with writers as well or do writers get to eschew that, along with blazers with pushed-up sleeves?

I think humor writers are generally much happier than standup comedians. I don't know why, exactly, but we seem to be less neurotic. Maybe it's because we tend to have more normal home lives, as opposed to traveling constantly and having to deal with hecklers.

3.10.2004

Office Romance

This week's very humorous Big Jewel piece is about a man who really likes his paper shredder.

Girl Talk

Last week's New Yorker contained a "Talk of the Town" piece about Yeardley Smith, who provides Lisa Simpson's voice.

An excerpt:

Smith is compact and petite, with kidlike features—eyes like frosted blueberries, pink lips, short blond wedge of hair. Her voice, though slightly squeaky, is not as high as Lisa's. People often beg her to do the Lisa voice on command ("Can you call my five-year-old daughter over the telephone and wish her a happy birthday as Lisa Simpson?"), but she needs a script to channel Lisa properly. To demonstrate, she grabbed a tin of Altoids from the dressing-room table and read from the lid in an aggrieved, hopeful lisp: "'The Original Celebrated Curiously Strong Wintergreen Artificially Flavored Mints.'" Lisa.

When Smith's agent wanted her to audition for Lisa, back in 1986, when "The Simpsons" was to be a series of short spots on "The Tracey Ullman Show," she balked. "I went, you know, 'I don't wanna!' My mind was still on being the most famous actress in the world, and that didn't include doing a cartoon." But she went anyway. "They said, O.K., super, you got the job, easy-peasy."

"My theory," she said, "is that Lisa Simpson is a reflection of most of our writers and the plight they survived as young people—that they were the smart ones, that they were different, that they were socially not as integrated, that they weren't athletic. I think they're all working out their own angst in Lisa Simpson." This month, while "More" is still playing, Smith will be taping Lisa's next season. "She's a great little girl—extremely bright and thoughtful and an old soul," she said. Lisa may be celebrating just her eighth birthday this year, but it's for the sixteenth time.

3.08.2004

Grand-Mall Caesars

The March 15 issue of The New Yorker contains a fascinating article on the history of malls.

An excerpt:

Well-run department stores are the engines of malls. They have powerful brand names, advertise heavily, and carry extensive cosmetics lines (shopping malls are, at bottom, delivery systems for lipstick)—all of which generate enormous shopping traffic. The point of a mall—the reason so many stores are clustered together in one building—is to allow smaller, less powerful retailers to share in that traffic. A shopping center is an exercise in coöperative capitalism. It is considered successful (and the mall owner makes the most money) when the maximum number of department-store customers are lured into the mall.

Why, for instance, are so many malls, like Short Hills, two stories? Back at his office, on Fifth Avenue, Taubman took a piece of paper and drew a simple cross-section of a two-story building. "You have two levels, all right? You have an escalator here and an escalator here." He drew escalators at both ends of the floors. "The customer comes into the mall, walks down the hall, gets on the escalator up to the second level. Goes back along the second floor, down the escalator, and now she's back where she started from. She's seen every store in the center, right? Now you put on a third level. Is there any reason to go up there? No." A full circuit of a two-level mall takes you back to the beginning. It encourages you to circulate through the whole building. A full circuit of a three-level mall leaves you at the opposite end of the mall from your car. Taubman was the first to put a ring road around the mall—which he did at his mall in Hayward—for the same reason: if you want to get shoppers into every part of the building, they should be distributed to as many different entry points as possible. At Short Hills—and at most Taubman malls—the ring road rises gently as you drive around the building, so at least half of the mall entrances are on the second floor. "We put fifteen per cent more parking on the upper level than on the first level, because people flow like water," Taubman said. "They go down much easier than they go up. And we put our vertical transportation—the escalators—on the ends, so shoppers have to make the full loop."

This is the insight that drove the enthusiasm for the mall fifty years ago—that by putting everything under one roof, the retailer and the developer gained, for the first time, complete control over their environment. Taubman fusses about lighting, for instance: he believes that next to the skylights you have to put tiny lights that will go on when the natural light fades, so the dusk doesn't send an unwelcome signal to shoppers that it is time to go home; and you have to recess the skylights so that sunlight never reflects off the storefront glass, obscuring merchandise.

Early "Man"

The following is from Ben Yagoda's About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made.

The final piece of this particular puzzle was James Grover Thurber, a native of Columbus, Ohio, who, in June 1926, was deposited in New York after a year's sojourn in Paris. He had some experience as a newspaperman, but his aspirations were literary and comical, and he began peppering the New Yorker with submissions. After being rejected twenty times in a row, Thurber was seriously considering returning to Ohio, deciding to stay only when FPA [Franklin Pierce Adams] devoted an entire "Conning Tower" to one of his New Yorker rejects. Soon after that he took a reporter's job at the New York Evening Post, and soon after that the New Yorker finally bought something he had written. The circumstances of that first acceptance are telling. The writer Joel Sayre, a close friend from Columbus, told Harrison Kinney, "I was lounging on a sofa in the Thurbers' apartment one Sunday afternoon in January 1927. Thurber had been working away at his typewriter on something he hoped to sell to the New Yorker. Althea [Thurber's wife] said to him, 'Aren't you spoiling your stories by spending too much time on them?' She suggested, half in fun, that he set an old alarm clock to ring in forty-five minutes and try to finish his article within that time. Thurber did. Then he retyped it cleanly and sent it off to the New Yorker. He received a check for forty dollars."

The rejected pieces are lost to history, but Sayre's anecdote suggests that their problem lay in their being labored, obvious -- not casual. The accepted one, titled "An American Romance," was so brief and offhand that few people reading the issue of March 5, 1927, probably even remembered it into the next day. But in the light of literary history it has an air of absolute inevitability. The piece begins:

"The little man in an overcoat that fitted him badly at the shoulders had had a distressing scene with his wife. He had left home with a look of serious determination and had now been going around and around in the central revolving door of a prominent department store's main entrance for fifteen minutes."

The little man continues to go around for two hours more, attracting, in turn, a crowd of onlookers, a pack of newspaper reporters, and an assortment of offers from motion picture companies. The whole ridiculous tableau mildly satirized the odd 1920s trend of English Channel-swimming, flag-pole-sitting, and the like. But the theme is immaterial. The astonishing thing about the piece is the way that first paragraph points the way to James Thurber's contribution to the New Yorker and to American literature. "The little man" -- ineffectual and quietly resentful in the face of the forces ruling his life -- would become the best-known creation of Thurber and, by extension, the New Yorker, culminating in the 1939 "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty." The throwaway reference to a "distressing scene with his wife" retrospectively sounds the starting pistol for Thurber's exhaustive, merciless, and meticulous three-decade chronicle of the war between men and women, especially between husbands and wives.

3.07.2004

A Fine Kettle of Fish

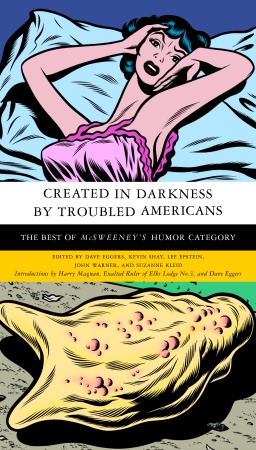

This hardcover collection of the best of McSweeney's Internet Tendency will be published in August.

3.06.2004

Editor, Regret-it-er

On March 3, the Wall Street Journal published this piece about William Shawn, the legendary editor of the old New Yorker.

An excerpt:

Few editors have achieved the iconic status of the late William Shawn, who ruled over The New Yorker for more than 35 years until shortly after the magazine's purchase in 1985 by S.I. Newhouse Jr. Many famous writers, including J.D. Salinger, Truman Capote and John Updike, saw their careers flourish under Shawn. One protégé compared him to Winston Churchill and even Mahatma Gandhi. Another, Renata Adler, wrote in 1999 that "The New Yorker since Mr. Shawn has been no one."

Through such encomiums, Ms. Adler and others did much to shape and tend the public persona of the secretive "Mr. Shawn" (as he was known to even his closest associates). "In Mr. Shawn I had found a literary guardian of impeccable taste, the soul of kindness and generosity," Ved Mehta wrote in his memoir. He was said to be so profoundly self-effacing that his mistress, Lillian Ross, recalled in her memoir of their time together how he would ask her "Am I really here?" Mr. Salinger, the most fervent acolyte of them all, declared Shawn to be the "most unreasonably modest of born great artist editors."

Arthur Gelb, longtime cultural czar and former managing editor of the New York Times, saw a different "Mr. Shawn," one he recounts in his recent memoir, "City Room." Mr. Gelb's memoir traces his 60-year career at the paper, when he witnessed many epic battles over such issues as the Pentagon Papers and the New York police corruption scandals. But the one that still rankles is the time back in the fall of 1966 when he went eyeball to eyeball with Shawn--and blinked. More than 37 years later, Mr. Gelb still seems to be rubbing his eyes.

"Little did we know what we were dealing with--we were innocents," he says with a shake of the head. "This great editor drove us to distraction."

One wintry afternoon at his office at the Times headquarters, Mr. Gelb sat fingering the frayed, yellowing proofs of the feature story on Shawn's New Yorker that he had assigned. It was one of his first initiatives as deputy metropolitan editor. The story was duly reported and edited, and a headline was composed to go with it. It never saw the light of day.

Word had been circulating that the venerable magazine was about to be bought by CBS. What greater journalistic coup, Mr. Gelb thought, than to commission a story on the enigmatic Mr. Shawn and his magazine. Eager to produce a thoughtful, in-depth New Yorker-like piece about The New Yorker, Mr. Gelb turned to one of his best reporters, Murray Schumach, and set him loose.

Almost immediately, a Damask Curtain descended. The fusty literary empire became impregnable. Writers were refusing to speak to Mr. Schumach; editors wouldn't give him the time of day. It soon became clear that the piece wasn't going to get done without Shawn's blessing, since no New Yorker staffer was willing to buck the boss. "Murray couldn't get to first base," Mr. Gelb recalls.

And Mr. Shawn wasn't going to cooperate without being allowed to read a draft--merely to check for "factual errors," he assured Mr. Gelb. In return, Mr. Schumach would be able to attend editorial meetings, interview Mr. Shawn--who was known to almost never grant interviews--and chat up his iconoclastic staff. (Mr. Schumach, now 91 and ailing, was unable to comment for this story.)

Mr. Gelb was being forced to make a pact with the devil. But he wanted the story. So reluctantly, realizing he was breaking with journalistic canons, he agreed. It seemed a small enough price to pay for the keys to the kingdom. The Damask Curtain lifted.

"It seemed too good to be true," Mr. Gelb says, adding ruefully: "It was."

Click here to continue reading.

3.04.2004

Lisa's Larynx

The following is from the theatre section of The New Yorker's "Goings On about Town":

YEARDLEY SMITH: MORE

Smith, the actress who provides the voice of Lisa on "The Simpsons," has written an autobiographical solo play, in which she stars. Directed by Judith Ivey. In previews. (Union Square Theatre, 100 E. 17th St. 212-307-7171.)

Note: "Yeardley" is pronounced "Yardley."

Channel 4 Channels 2

The British newspaper the Independent reports that Channel 4 is making a TV movie about Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. (Via Mike Gerber.)

Excerpts:

Rhys Ifans, the actor best known for his portrayal of Hugh Grant's slob flatmate in the movie Notting Hill, will play Peter Cook in a "warts and all" Channel 4 film about his up-and-down relationship with fellow comedian Dudley Moore.

Not Only ... But Always explores the pair's life together - from their first meeting in the 1960s to Cook's death in early 1995, aged 58. Their often tempestuous partnership has been condensed into just two hours, and chronicles the pivotal moments in their careers.

Moore, the diminutive "sex thimble" who died nearly two years ago at the age of 66 from complications arising from a degenerative illness, will be played by the little-known Aidan McArdle, who has worked mainly on the stage.

=========

[Executive producer Charlie] Pattinson said of the film: "Predominantly it is Peter's story, but the emotional spin on the story is the relationship between Peter and Dudley, which has that sort of 'every relationship' quality to it whether you knew who they were or not. It's a marriage that explodes then comes back together and then explodes again.

"It uses markers from their creative life to tell the story, such as Beyond The Fringe, Not Only ... But Also, and it touches on Dudley's film career and Peter's less successful years."

Filming begins a week on Wednesday and will take place almost entirely in New Zealand, which will double for locations as diverse as Cambridge, New York, Los Angeles, where Moore made his home, the Caribbean, where they wrote together, and Exmoor.

Channel 4's head of drama, John Yorke, said: "It's a history of British comedy, a look at the psychology of a relationship and a portrait of post-war Britain - but most of all it's the story of Pete and Dud."

Homer Box Office

From Sky News, February 11, 2004:

SIMPSONS TO HIT BIG SCREEN

America's most famous dysfunctional family, The Simpsons, are finally to appear on the big screen.

After years of speculation, Simpsons creators Matt Groening and James L Brooks are leading a team of writers in developing an animated movie.

According to industry insiders, Al Jean, Mike Scully, Mike Reiss, David Mirkin and George Meyer are all on board.

Work has already started on the script but the plot line is not yet fully formed.

It is expected to be a longer more amplified version of the show similar to the concept of the South Park movie.

Chris Meledandri, 20th Century Fox's animation chief, said the team are "very excited about the possibility of making a Simpsons movie".

"However, we are in the very early stages of developing an idea for the movie," he added.

There is no clue yet as to a release date on the movie, but it is expected to be at least two years off.

3.03.2004

On the W.C.

Click here to listen to a fifty-minute conversation about W.C. Fields with James Curtis, his biographer, and Ron Fields, his grandson. This interview was broadcast on The Diane Rehm Show on September 12, 2003.

3.02.2004

Poster Roaster

My pal whitney pastorek wrote this Village Voice essay about how blogs are ruining her life.

An excerpt:

A step down from Denton's cabal are blogs like TMFTML (The Minor Fall, the Major Lift), independently run by some guy sitting in a room. Sort of the P. Diddy to Gawker's Sting, they remixed the hit song and made it . . . different. Plus he maintains total anonymity—which really pisses bloggers off. On his level are sites like Cup of Chicha, Old Hag, or the Elegant Variation. Here, you're less likely to find breaking news about media culture, but you will learn a lot about the drinking patterns of articulate twentysomethings. They're all friends, the bloggers on this level, and they're in a constant state of link-swapping, making it possible to actually click through the Web in a giant circle all day, like Tigger bouncing through the Hundred Acre Wood.

I don't know all of this because I am a blogger. I know it because my friends are, and now everything is bad. And while a lot has been made of the cultural implications of the Blogosphere, I am not convinced that anyone has taken the time to talk openly and honestly about the effects it is having on the day-to-day existence of the world's adult non-bloggers, or what I like to call The Way Blogs Are Ruining My Life.

3.01.2004

Homestar Runners

Here you can listen to a Wired News radio interview with the creators of the Homestar Runner site.

The Everyman

Click here to listen to a discussion of Peter Sellers with Ed Sikov, author of Mr. Strangelove: A Biography of Peter Sellers. This interview was broadcast on the January 31, 2003, episode of The Leonard Lopate Show.

Here is Michael Palin's New York Times review of Mr. Strangelove.